Since I have an interest in teaching my primary advisor and I worked together to ensure that my supervised teaching experience was more than a semester of grading papers or leading lab activities. We selected a module about descriptive statistics and data visualization from her Introduction to Agricultural and Biological Engineering course that I was to create and deliver the lecture, lab, and homework assignment for.

Before I started my master’s I had never even attempted programming anything, now towards the end of my Ph.D. most of my activities are programing. I hadn’t even expected this trajectory, but I am thankful for a few experiences along the way that gave me the skills to write code and solve problems in what I write. Most of them stem from the classes I took, and the teaching methods I observed in them. They taught me how to make programming approachable, the reasons code works the way it does and how to make learning the basics relevant to others. I wanted to take a moment to focus in on these things and how I recently incorporated them into my teaching.

Jupyter notebooks as an educational tool

The goal of this module was to have students be able to describe and visualize datasets, with the twist of not using Excel. Having graded an assignment that involved programming earlier in the semester I knew that the programming skill varied widely so I would need to consider this as I developed the materials. Strangely enough I ended up developing the materials backwards, with the assignment informing the lab activities, which guided the lecture materials.

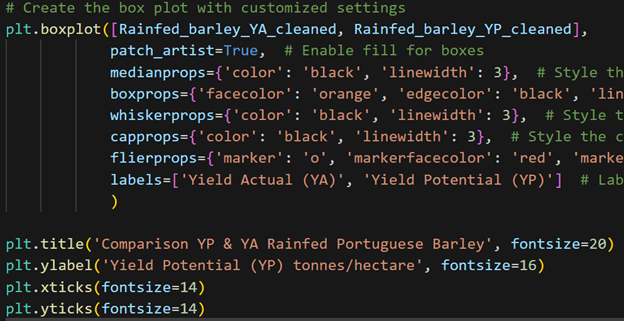

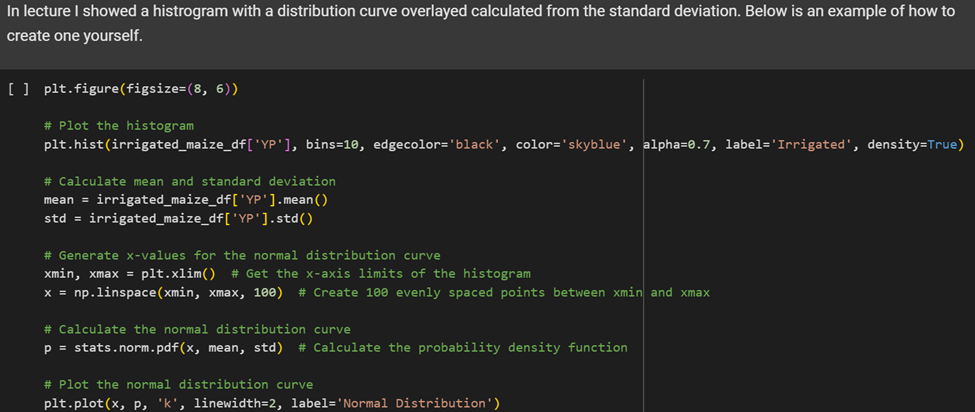

The assignment was downloading a dataset from the Global Yield Gap Atlas’s website, analyzing the yield potential and yield actual of the crops and discussing the yield gaps they found. From there I built a Jupyter Notebook in which I essentially completed the assignment for the United States. It covered everything step by step from uploading the data to cleaning it up and plotting it, with the idea being that any student who didn’t know any programming prior would be able to follow along and duplicate everything. Inspired by a class that was entirely taught out of notebooks, mine also served as the basis for the lab portion of the class, I could walk them through everything in detail, but later they could look at the notebook and receive the same instruction.

An interesting side note is that the notebook I provided could have been easily altered by uploading a different dataset, and changing instances of “United States” to whatever country they picked. I expected a fair number to do this as it was even encouraged since the goal was data interpretation not programming. A few of them did, with the rest instead opting for the challenge of programming their own version, some of which had no issues at all, but I was there to help with any issues.

Mistakes, Troubleshooting, and Patience

In theory everyone shouldn’t have had an issue completing the assignment, but reality rarely works that way. For starters I had to send out additional code for them to clean their data sets since the one I used to build the notebook didn’t encounter NaN values, but many of their datasets did! Fortunately, that fixed many of the issues, and beyond that I did have a few students come for office hours where I emulated my first coding instructor. I spent a lot of time at office hours with him troubleshooting my code and learning the nitty gritty details about programming. If it wasn’t as simple as a capitalization error, he rarely gave me the answers directly and instead he would glance at my code and help me understand the error and why it was occurring.

To my surprise, often I could also effortlessly find the error with a quick scroll without running the code. From there I found myself falling into the same patterns, no matter how simple the error, I made sure they looked at the error message and explained what it meant. If that didn’t lead them to the answer I would explain the reason for the error, leaving them room to reach the solution. Simply giving the solution would have been exponentially faster, but I never felt the need to rush the process as they likely wouldn’t have learned as much. It was nice to show the same patience I was given years ago that helped me so much.

Programming over Excel

One thing that I incorporated into the lectures and the office hours was how these are often the same processes you would follow in Excel. I have found this concept is often missing from many teachings of programming, which is a shame as most students when asked to analyze and chart a dataset wouldn’t even think before opening Excel. Expert users can do amazing things quickly, but for most of us it requires lots of copy, paste, sort, delete, rearrange, and oh so much clicking.

The key takeaway I made sure to drive home was that the same process in Excel would likely be untraceable without lots of written comments and messy sheets. If they needed to duplicate or modify the charts in a few weeks or months, they might have no idea how exactly or what they even did to the dataset. However, with programming the original data is intact, and the script is already step by step instructions on how to do it again, that they could use for themselves, or even give it to someone else to show them the procedure.

Conclusions

The Jupyter Notebooks idea came from a class about non-linear data diagnostics, a subject that would have been completely beyond me but was excellently designed and delivered through a series of self-contained notebooks. The patience and use of troubleshooting as a learning experience comes from a bioinformatics course, a subject I have yet to ever explore further, but the programming skills from it are used daily. The last bit about comparing programming to the processes students are likely already using is just something I realized as I found myself doing things in python that I would have done in Excel 6 years ago.

I personally feel that students should be leaving college having learned to program, even on a basic level. I can’t even think of any degree type that wouldn’t benefit from basic programming skills. While teaching methods should vary across disciplines, and may seem daunting to some teachers, incorporating these practices into instruction doesn’t take much effort and can greatly improve the quality of instruction and learning outcomes for students.

Proudly written without large language models.

©Donald Coon 2024 available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14253618

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0