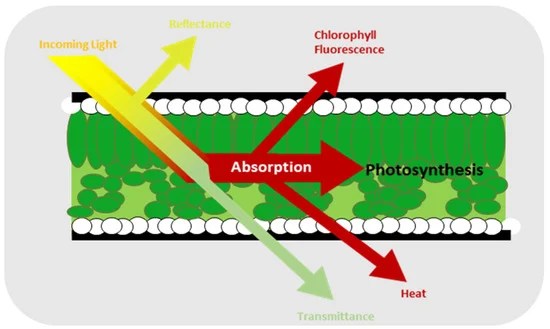

When light hits an object the photons will either be reflected off it, transmitted through it, or be absorbed by it. When talking about plants, the absorption part is quite interesting because it adds a few more possible fates than the roof of a building. When light is absorbed by a leaf, there are then three possible fates; 1) Chlorophyll catches the photon and uses its energy to conduct photosynthesis. 2) The excess energy is dissipated as heat. 3) Fluorescence, where a photon is re-emitted at a lower energy. Those fluoresced photons are the basis for one of my favorite techniques I have learned about and used during my research.

How Chlorophyll Fluorescence is Done

The image above is a typical fluorescence trace; it starts off with a dim measuring light being turned on (MB) to capture the minimum fluorescence level (Fo). From there a pulse of light saturates the leaf (SP) to determine the maximum dark adapted fluorescence level (Fmo). Then an actinic light (AL) is turned on which drives photosynthesis for a bit, right before another saturating pulse is applied to determine maximum light adapted fluorescence (Fm’) fluorescence is measured again (Ft). The last thing that happens is the actinic light is typically replaced with a far-red, and the light adapted minimum fluorescence is measured (Fo’).

110 Photons Walk Into a Leaf…

Suppose 110 photons are heading toward a leaf, when they reach it, we will keep our lives, and math, simple by saying 6 photons are reflected off the leaf, and 4 pass through it entirely leaving us with a nice round 100 absorbed photons (purely hypothetical numbers). Knowing the fate of those 100 photons would be very useful to model photosynthesis in the prediction of crop growth and yield, but it can’t be paused and deconstructed to quantify it. Fortunately, we can indirectly observe it through chlorophyll fluorescence.

By shining light at the plant and measuring how much comes back, in the manner shown in the Figure 1, we can now make some calculations to help fill in these gaps. Using (Fm’ – Ft)/Fm’ from the fluorometry tells us that the quantum yield of photosystem II (ΦPSII). Non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) can be calculated with (Fm − Fm′)/Fm′ and reflects heat dissipation of from photons not used in photosynthetic processes. What remains are other energy dissipating pathways such fluorescence or the formation of harmful by product, such as reactive oxygen species. Best part is that these three things account for the possible fates of our 100 photons! So, if we know ΦPSII equals 65, and because we kept the numbers simple, that means 65 photons were used for photosynthesis.

Conclusion

To me it is quite cool to be able to use simple flashing lights to determine the amount of photons being used in different processes within a leaf without needing to damage the plant in question. Being able to measure how many photons are being used in photosynthesis is just an amazing ability to have, especially if you are trying to quantify how much photosynthesis is happening.

There are surprisingly many discoveries and tools that are built around the flashing of light and what comes back or doesn’t. As our ability to precisely emit and measure photons increases, so will the amount of information we can gather about the world around us.

Reference

Kate Maxwell, Giles N. Johnson, Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide, Journal of Experimental Botany, Volume 51, Issue 345, April 2000, Pages 659–668, https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/51.345.659

©Donald Coon 2025 available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18111031

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0